Treating the "Untreatable"

Why OCD treatment sometimes fails, and how we can improve it.

Written by Sam Greenblatt, Psy.D.

01 Many patients with OCD who have gone through exposure and response therapy have found that they do not respond to treatment.

02 Dr. Greenblatt explains the different approaches to ERP, Emotional Processing Theory vs Inhibitory Learning Theory, and how these implementations can affect the success of treatment.

I treat many patients who report they’ve been to an obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) specialist who used exposure and response prevention (ERP), and even after diligently completing all assigned therapy homework, they: 1) Saw no results 2) Had dissatisfying results or 3) Rebounded to their previous level of OCD within a short period of time following termination.

Rest assured, this is a pattern outside of my personal experience. While the non-response rate to ERP is great compared to other treatments, it remains that 14-31 percent of clients do not respond to treatment. Even more alarming is that 50-60 percent of clients report undergoing at least a partial relapse after treatment!

Over my years of treating hundreds of patients, reviewing well-established research of the past 15 years, and receiving guidance from some of the most brilliant OCD specialists of our time, I am confident as to why this occurs and what can be done to remediate this pattern. OCD treatment is so effective because we’ve created a brilliant form of therapy for it, yet OCD treatment is falling short because we are implementing the treatment in an unoptimized and problematic way.

Choosing Exposure Response Prevention (ERP) Therapy

Emotional Processing Theory: Well Intentioned And Outdated

This happens a lot in the field of healthcare. Famously, many medications were developed not because scientists knew exactly how or why they worked, but rather discovered that they do work, and afterwards developed theories as to why. Sometimes the initial theories are correct and sometimes they are not. For years now, research has frequently shown that the model developed for explaining the effectiveness of ERP has many holes in it.

If you’ve gone through unsuccessful ERP-based treatment, you were probably taught how it works along the following lines: The root of OCD is that a broken alarm plays in the brain, warning against a proposed danger, and the OCD sufferer responds to that signal with a distressed reaction (compulsing). This is treated through exposures, where the client resists the urge to compulse when they are triggered. As a result of doing so, the client unpairs the brain’s connection between the OCD theme and distress, and the distress goes away.

The problem is, this rationale has long been disproven. A number of studies show that:

- Habituation is not related to treatment outcome

- Complete habituation is not often possible

- If the patient’s OCD theme switches, the client will have to start from square one as habituation to a former theme would not apply to the new one. (This point in particular may be why relapse after OCD treatment is so high).

Along with these fallacies comes another issue. Placing pressure on the exposures to reduce distress makes them more likely to become targets of obsessions. Clients become more likely to obsess that they are doing exposures incorrectly and worry their distress will never die down. They may develop compulsions around their exposures, such as doing them more frequently, to try to assuage that fear. Of course, as all compulsions do, this only makes the OCD worse.

Lastly, the ERP model reinforces the maladaptive concept that anxiety is bad and undesirable. As with many thoughts and feelings, the more power we lend a concept by dreading it, the more likely it will pop up.

So all hope is lost — ERP has a huge relapse rate, and the theory used to explain it is built on a flimsy premise. But wait! ERP still works, and it has amazing success rates even though EPT can’t explain why. If we can figure out what is really fueling the effectiveness of therapy, we can take a great treatment and enhance it even further.

Along Comes Inhibitory Learning Theory

Inhibitory Learning Theory (ILT) is by no means a new and untested theory. A landmark paper on ILT for OCD was written back in 2008, and since then, this approach has gained more and more support, with some of the most reputed OCD researchers of our time contributing to its development. A quick academic search of OCD treatment articles written in the last ten years will show a trend of enthusiastic support for this theory. Sadly, as with much of the healthcare world, there is a sizable gap between research and practice. As a result, many modern practitioners have not yet heard of this years old shift in theory.

The premise of ILT is built around fundamental truths in psychology: New learning does not replace past learning. What this means is that when we learn to sit with anxiety without performing compulsions, this doesn’t make the brain forget that it was once distressed by these signals.

Here’s a metaphor to explain what I mean: I used to have a contentious view of my dad, but now we have a great relationship. Though our present relationship may be better, it doesn’t make me forget the difficulties we had in the past. Occasionally, my dad will say or do something that elicits difficult feelings in me that used to be more frequent in our relationship, but this distress is no longer the default response. Instead, the closeness I have with him today is the louder of those two voices.

The same goes for OCD treatment. Because someone with OCD has a broken alarm system in their brain, they may always have a predilection to experience a false alarm that something is wrong. However, through exposures, they can learn a new way of relating to those signals that becomes the default response they naturally turn to.

By structuring ERP to work in this way, we can expect much more consistent results. No longer do we view the results of therapy as dependent of a variable we are not in direct control over (our emotions). Instead, the goal of therapy is very logically within our grasp: establishing a healthier relationship to anxiety by learning how to relate to it in a different way.

When we learn to ascribe irrelevance to the brain’s broken signals by not responding to them, we rob those signals of any power or influence they have over our lives. The end result is practicality the same as if the distress was abolished, and the patient's life goes on unaffected and untarnished by the OCD signals. They become empowered to navigate throughout life as if the signals never even existed.

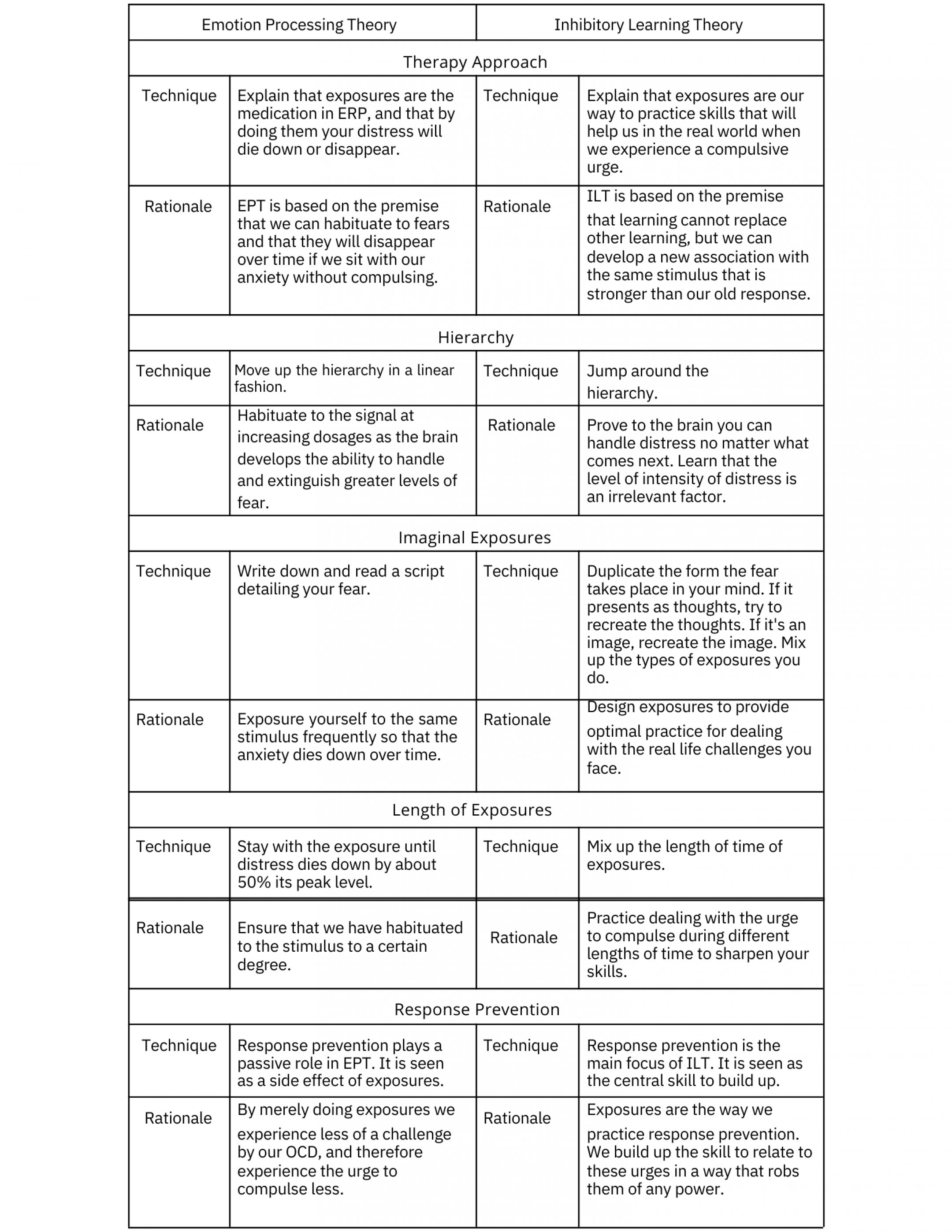

So what does this look like when it comes to the differences between how ERP is conducted? Below are some of the important changes that are made to therapy when we switch from an EPT model to an ILT one.

By conducting therapy in a more effective way, we can likely not only expect more consistent results, but longer lasting ones as well. This is all to say that if you have OCD and have received ineffective ERP treatment, there is absolutely still hope.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

This article was written by Dr. Sam Greenblatt. To contact him, you can email him at [email protected]. To check out his other works, you can view a list of articles at his site, www.drsamgreenblatt.com.

Support our work

We’re on a mission to change how the world perceives mental health.