The Unseen and Unerasable: Cristi López on Bringing Intrusive Thoughts to Light

We chatted with the artist about how she’s using art as a tool for education and recovery.

Written by Esther Fernandez

01 Cristi is a Florida-based artist with OCD. Her first solo-exhibition, “Unravel: Portraits of My Obsessions” includes 15 paintings about her relationship with her mental health.

02 Copywriter Esther Fernandez interviewed her about her journey with art and OCD, the motivation behind her exhibition, and words of advice for anyone who might be struggling.

03 Cristi’s exhibition will be open April 7 - May 13 at A Very Serious Gallery in Chicago.

Can you start by telling us a little bit about yourself and why you decided to become an artist?

My name is Cristi López. My parents immigrated from the Dominican Republic before I was born. We started out in New England, but eventually moved down to Florida, and I've lived here since then. As far as starting to create art, it was just something I'd always turn to when processing my emotions. It wasn't until I gained awareness around the pressure to become a “talented artist” that my relationship with it became more strained. For a while, it was hard to enjoy the process, especially with OCD and perfectionism. I would say in the last ten years since I've started doing this in a more serious capacity, I've found ways to manage the anxiety.

As we're gravitating toward the topic of OCD, can you tell us about your mental health journey?

My first distinct OCD memory was around the fear of causing pain to others. I was a sleepwalker, so I would frequently walk out the front door or talk to people in my sleep, and have zero recollection of it. I was very young, maybe in elementary school, and having thoughts like, "If I don't know what I'm doing in my sleep, what's keeping me from hurting my family?"

I had very vivid intrusive thoughts of going into the kitchen, taking the knives and killing my family in my sleep. I would make my parents hide all of the sharp objects in the house. And naturally, because they didn't realize that that's a pretty glittering sign of OCD in a child, they went along with it.

That was one of the more detectable and overt symptoms, but there were always a lot of internal rituals around magical thinking. Thought processes like, "If you don't do this, then this is going to happen." As I got into my teenage years, I think I learned how to navigate the world in ways where people couldn't tell so much.

Photo credit: @maxine.worthy

When it comes to mental health struggles, I feel like a lot of us want to appear high functioning and keep it all in our head — which brings me to your art exhibition. Can you give an introduction to your pieces?

This is actually my first solo exhibition, and the intention of the show is to portray the internal experiences of someone with OCD in ways that usually aren't represented. I wanted to show the emotions, complexity, and creativity that is often inherent for people with OCD. Not as a positive, but moreso, to humanize people as being more than just their condition.

The gallery is also partnering with the Chicago chapter of NAMI to have mental health resources and a lecture panel. We wanted people to come into the space for the art, but also, serve as a bridge for them to learn more.

This being your first solo exhibition, you could have chosen any topic. What was the motivation behind focusing on mental health, and specifically your OCD?

I don't always consciously decide to focus on mental health, but my work has always been about my internal journey through manipulation of the human figure. It was kind of a no-brainer when it came to the topic, and my vision for it was pretty locked in — making the exhibition a vehicle for accessing different resources. That was the special piece I knew I needed when considering what gallery to work with.

Chicago is a wonderful city with a lot of diversity, but at the same time, there's so much disparity between ethnicities and socioeconomic classes. It was really important for my art to be in a space that is committed to community unification. The gallery I'm working with, A Very Serious Gallery, does a lot of different community based programming such as poetry or music nights. They really showcase the diversity of the city in what could be a very cold or clinical environment, which is what a lot of galleries have become. I'm not super interested in these quote on quote, "galleries" or "the art world."

I feel like "the art world" is the same as "the clinical world" when it comes to mental health. You have people saying you need to be in specific spaces for treatment, but they're expensive and inaccessible. Or conditions are presented as cold and clinical, when in reality, mental health is the complete opposite. It’s supposed to be human and nuanced.

I want to backtrack when you talked about portraying internal experiences. You say in your description of this exhibition that not only do you want mental health to be visible, but you also want to reclaim power and take up space. Two reasons this stuck out to me: 1) Making mental health tangible is an interesting challenge to take on 2) OCD, especially with taboo intrusive thoughts, is full of so much shame. It's not something people typically feel comfortable speaking out about or reclaiming power over.

How did you manage to take these really big, abstract, heavy feelings around OCD and turn them into empowering art pieces?

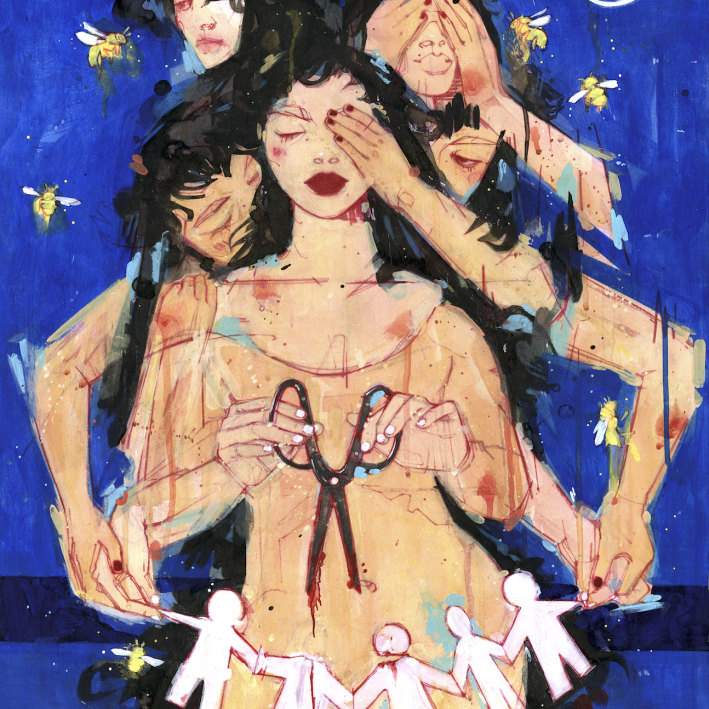

I think people with OCD tend to be sensitive to certain kinds of imagery. Our brains attach themselves to the minutiae that other people might not pick up on. It was really important for me to create art that resonated with that emotional experience, but wasn't overly triggering. A motif I use a lot is scissors — they represent the potential danger people with OCD often feel.

The moment that you introduce an object into a painting, the mind immediately goes, "Okay, what are they going to do with that? Will the subject cut or stab something? Are they violent?" I really like the ambiguity and maybe even confusion that scissors present in the artwork, because often with OCD when we see certain objects, we assign this very rigid meaning to them, when in actuality–

It's just an object.

Exactly! And the context for that object changes depending on how you present it. With scissors, I could barely look at them when I was younger because all I could see was intrusive thoughts of me stabbing my family. As I grew up and began creating art, I drew scissors because I wanted to reclaim symbols that once represented my worst fears.

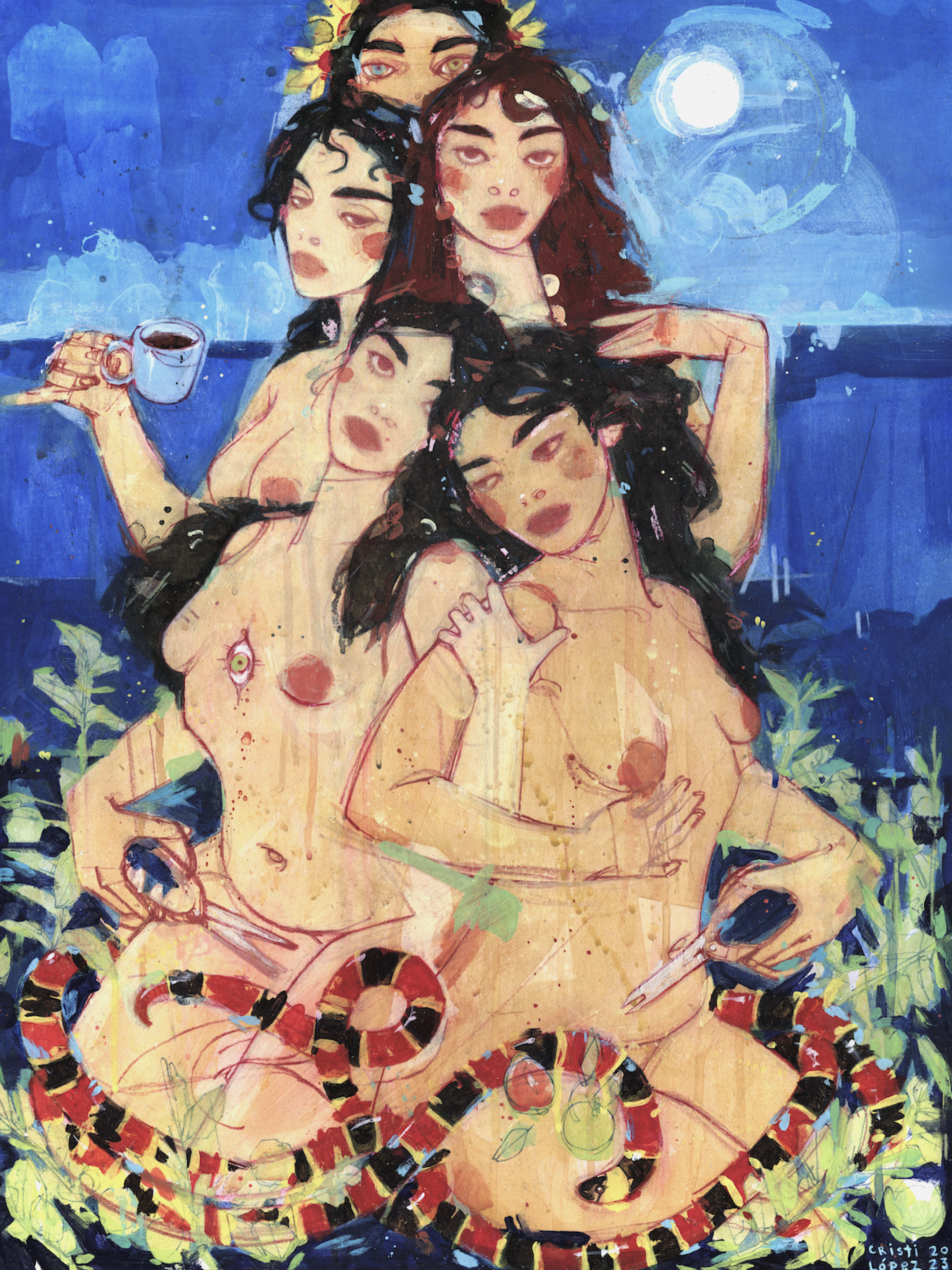

You also have a lot of women in your pieces, and you use both “power and vulnerability” to describe them. At surface level, those words seem contradictory.

So many of the artists that I grew up loving and admiring were men, because primarily, male artists have been preserved in historical archives. But when I was coming of age, I started seeing things I didn't see before. I became more aware of power dynamics and had my own sexual experiences, and realized I didn’t like all of these depictions of women being sexualized and infantilized.

As I became a woman, I didn't want to perpetuate that image. Not to say that women can't be soft and vulnerable, but I also wanted to show them in their immensity and complexity in a way that wasn’t just mimicking the poses of men or being these approximations of male strength.

I think part of the strength and beauty of women is that it includes chaos and expansiveness and all these things that so often have negative connotations when attached to women. So even though they're nude, they're not being coquettish — they just unapologetically are. And if I do portray a woman as vulnerable, I want it to read as emotional vulnerability, not sexual vulnerability, because I think we don't need more images of that.

I feel like what you're getting at is that women are human. We don't need to be objectified or sexualized. Sometimes our bodies are going to be naked, but nakedness doesn't have to mean fetishization. And empowerment doesn't have to mean emulating men.

You talk a lot about how art has helped you in your mental health journey and processing your experiences. How can people incorporate art into their recovery, especially if they don't feel particularly artistic?

When I was in the depths of my disorder, I remember the idea of creating art felt impossible. At that point, I felt like I succeeded if I took a shower, so how the hell am I going to create a masterpiece?

Something I started doing in college — which revolutionized my art practice — was doing everything I could to combat perfectionism. I made myself draw with uneraseable media for six months. I bought sketchbooks that you can't tear pages out of without compromising the binding. I let myself make ugly drawings, and had to let them live in my sketchbook. The first few times I would look at them, I'd say, "I'm literally the worst artist that has ever existed." But by the 100th time, it got easier. Kind of like an exposure.

My advice is to take baby steps around the things that you love. If I were to pick up my sketchbook and say, "I'm going to make the most beautiful drawing I've ever made in my entire life", that's not realistic. So if you're really struggling and telling yourself, "I want to make something of this, but everything feels insurmountable. It hurts to move. It hurts to breathe. It hurts to be awake." Just pull out a piece of paper and a pen, and draw your hand. Draw the door. Pick something small. If you're a photographer or a musician, find the equivalent to that.

That's a really good reminder to have when you're in survival mode.

Absolutely. We don't live in a culture that respects the ebbs and flows of being alive, and that's something I really want to emphasize to people.

You're going to have those highs and lows, and you need to give yourself permission to mess up. Especially as someone with OCD, when everything is so black and white. I remember having a conversation with my therapist once about everything seeming so big and impossible. She said, "Why are you aiming for 100%? Why not be 1% open to change?" I realized that 1% of openness is the difference between sitting in complete darkness, and allowing some light to enter.

Knowing all of this, if you could talk to the younger version of yourself, what would you tell her?

You will find a way to reclaim your most painful experiences, and it will make you so much more powerful and self assured than you could ever imagine. All the things that people don’t understand and make you hate yourself? Don’t reject them. Find a way to integrate them and use them for good. You're going to help a lot of people by bringing light to those shadows you are so intent on hiding from everyone.

I always tell people that the greatest exposure is becoming an artist or an advocate, because the moment you put it out there, you can't really take it back. In our brains, we're like, “What if everyone interprets it incorrectly? What if someone doesn't actually think it's intrusive thoughts and I'm this awful person? What if I get arrested?” Haha.

I remember when I first got diagnosed and was being interviewed for an independent magazine, I had so much OCD around my diagnosis and thinking that I was lying. I told the interviewer, "Please don't publish that I have OCD, because I have a lot of shit that I need to figure out." It's incredible how four years later, I'm talking about it so openly. I’ve realized the thing you want to do the least is what ends up helping and freeing you the most.

<>

Cristi can be found @cristi.lopez.s on Instagram.

Her exhibition will be open April 7 - May 13 at A Very Serious Gallery in Chicago. To find out more, visit veryseriousgallery.com

Support our work

We’re on a mission to change how the world perceives mental health.