I’m (Actually) So OCD

Living with OCD has been the biggest challenge of Alicia’s life. Stigma and shame forced her to keep it hidden — until now.

Escrito por Alicia Devine

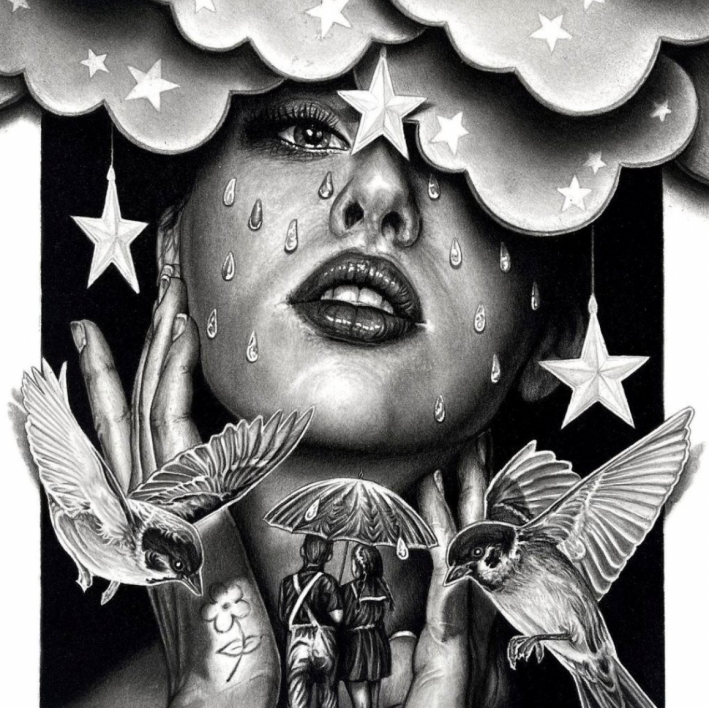

01 Alicia has struggled with intrusive thoughts since childhood.

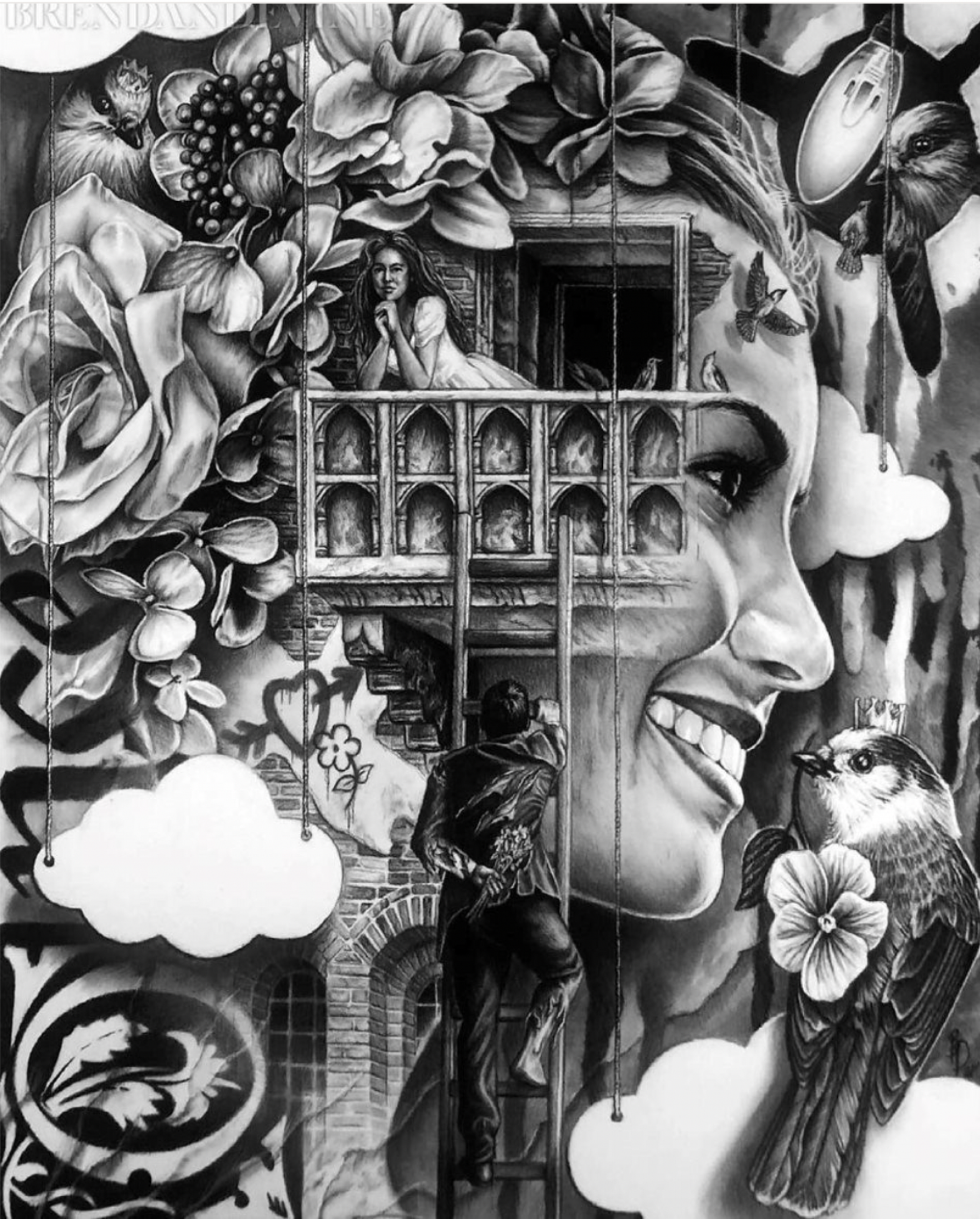

02 After leaving college because of her mental health, she sought therapy but struggled to find any relief. A Google search helped her realize she had OCD.

03 While it took some time to find the right therapist, she eventually received an OCD diagnosis and began exposure and response prevention therapy.

04 Art credit to Brendan Devine, Alicia's partner.

TW: Sexual abuse

I was a good kid. Conscientious, perfectionistic, sensitive — a people pleaser at my own expense. I worried a lot, but didn’t want to worry others. I once let go of my favourite Spice Girls trading card because someone else said they wanted it.

At around age five or six, I was sexually abused on several occasions. I didn’t know it was abuse at the time, but its impact on me has been enduring. Soon after, OCD symptoms started surfacing in the form of needing things to feel just right — a common manifestation of the disorder. Clothing needed to sit in a spot that felt “just right.” Turning my body in one direction required me to turn in the opposite direction to feel “just right.”

I experienced my first significant episode of OCD on a family vacation when I was 12. Like many others, there was a single moment where, for no apparent reason, my brain got stuck. A painful loop of unprovoked thoughts entered my head like a song on repeat. They were persistent, invasive, and sucked all enjoyment out of the present moment. I worried that these thoughts would never go away.

I still managed to do well in school, achieving high grades and earning entrance scholarships. My OCD would occasionally taper off on its own, but it would reappear during periods of stress, change, or unstructured time. Despite my turbulent mental state, I moved to Toronto to study business and did my best to ignore the intrusive thoughts.

One night while studying for a calculus exam, I couldn’t manage to stay focused for more than a few seconds. A severe panic attack led to an ambulance ride to the hospital. I was told I was experiencing anxiety and depression, and was prescribed antidepressants. I did not make it to my calculus exam, or any of my other exams for that matter. I instead left the city to try to get better.

After leaving school because of my mental health, I felt broken, and emotionally beat myself up for being ungrateful about all the wonderful things I had in my life. What was I sad and worried about? There were people who had real problems. I was painfully, rationally aware of my irrationality.

I eventually decided to seek therapy, opting for a local psychologist-in-training to cut on wait time and cost. He would ask me exploratory questions, attempting to solve my concerns. But each time I left, I ended up feeling worse than when I walked in. Something wasn’t adding up. In a desperate state one night, I turned to Google and typed, “Thoughts I don’t want to have.” My attention immediately focused on one search result: intrusive thoughts.

This felt descriptive. I replaced my original search with this term, and it led me to an article that changed my life forever.

For the first time, I was reading words that described exactly what I had been going through. The author explained OCD as a disorder where the brain’s amygdala is hypersensitive to danger and mistakenly overemphasizes the need for certainty to feel safe. Like a burr, OCD hooks onto the things that are most meaningful to people — health, morality, religion, relationships.

Now that I finally had a name for what I was going through, I decided to try therapy again. I found a local psychologist who had experience in treating OCD and, despite the cost, booked an appointment.

“So, I understand you believe you have OCD,” she said. “Yes,” I replied, holding on tightly to my printed pages of black-and-white proof. I described to her what I had discovered and handed her my papers. She said that while everything I presented made sense, she wasn’t familiar with these expressions of OCD. My heart sank. I had fantasized about her saying she treated many people just like me. While we did end up working together for a few sessions, her limited experience with Pure O caused me to put my walls back up.

Despite my quiet struggle, I got on with life, and slowly the intensity of OCD dissipated. I was reaccepted into another university, graduated, advanced at a national non-profit, and found love. I was seemingly unaffected by mental illness from the outside, but it always lingered under the surface, waiting to reemerge. At that point, I had never been officially diagnosed with OCD and would question whether I actually had it. Whenever it would flare up, it made me want more firm answers, and a path to recovery.

A social worker from my doctor’s office helped me arrange an appointment with a psychiatrist. I walked into his office with my laptop, ready to share a meticulous timeline of my symptoms. Instead, he asked me to put the computer away so I could speak freely and from the heart. I was intensely uncomfortable at first, but he was right. He didn’t need to know every detail to understand what I was experiencing.

“So, do I have it?” I asked. He looked at me for a moment. “Yes,” he replied with confidence, “and the fact that you asked me that further proves it.” He changed my medication and recommended a free group cognitive behavioural therapy education course. After years of unhealthy thought patterns, I began to make a dent in the hardened metal.

When the pandemic started, I was engaged to a wonderful man and we were planning to start a family. This was the most anticipated chapter of our lives, but the pandemic had created a breeding ground for anxiety. If I was going into this new chapter, I needed to do everything I could for my partner and future kids. And there was something I hadn’t done yet: exposure and response prevention therapy.

The premise behind ERP is that you build irrelevance to intrusive thoughts by gradually exposing yourself to triggers, and subsequently refraining from compulsions. Over time, your brain learns that thoughts are just thoughts and the overattachment to them isn’t necessary.

Meeting with my new psychologist provoked intense anxiety. However, I trusted this experience would be different. My therapist understood and validated the intense struggle of coping with OCD. She created a well-structured plan to help me get better — educating me on the OCD cycle, building a case for why I wanted to do ERP, creating and facing a hierarchy of exposures. I began to feel more confident, and in anticipation of getting pregnant, I slowly weaned off my medication.

Art credit: Brendan Devine, Alicia's partner.

Unfortunately, after participating in a rigid diet program this year, my OCD pushed itself back up to the surface. I ended up needing to take time off work to recalibrate. I met with my therapist more often, meditated daily, and attended OCD support groups for the first time.

Previously, I thought that recovery meant not having to deal with intrusive thoughts and completely self-managing my illness without the help of medication. Now, I know that I will experience ebbs and flows of OCD whenever major life events inevitably occur, and I’ll have the tools and support to help me get better.

I’ve also realized that hiding makes things feel inherently dangerous, even when they’re not. So here I am, representing myself as someone who experiences this disorder in hopes of helping others who are in the same position. Suffering with purpose makes my journey with OCD bearable, and maybe even worthwhile.

<>

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alicia is a people operations leader at a charitable organization. She lives in Guelph, Ontario, Canada, with her partner, Brendan, and their dog, Pepper.

Apoya nuestro trabajo

Nuestra misión es cambiar la manera en que el mundo percibe la salud mental.